Address Poisoning: The Growing Threat Draining Millions from Crypto Users

Address poisoning has emerged as one of the most persistent and damaging threats in the crypto ecosystem. What once began as a relatively crude social engineering trick — planting lookalike addresses into a victim's transaction history — has evolved into sophisticated, multi-chain campaigns backed by dedicated tooling, automation, and a dedicated underground supply chain.

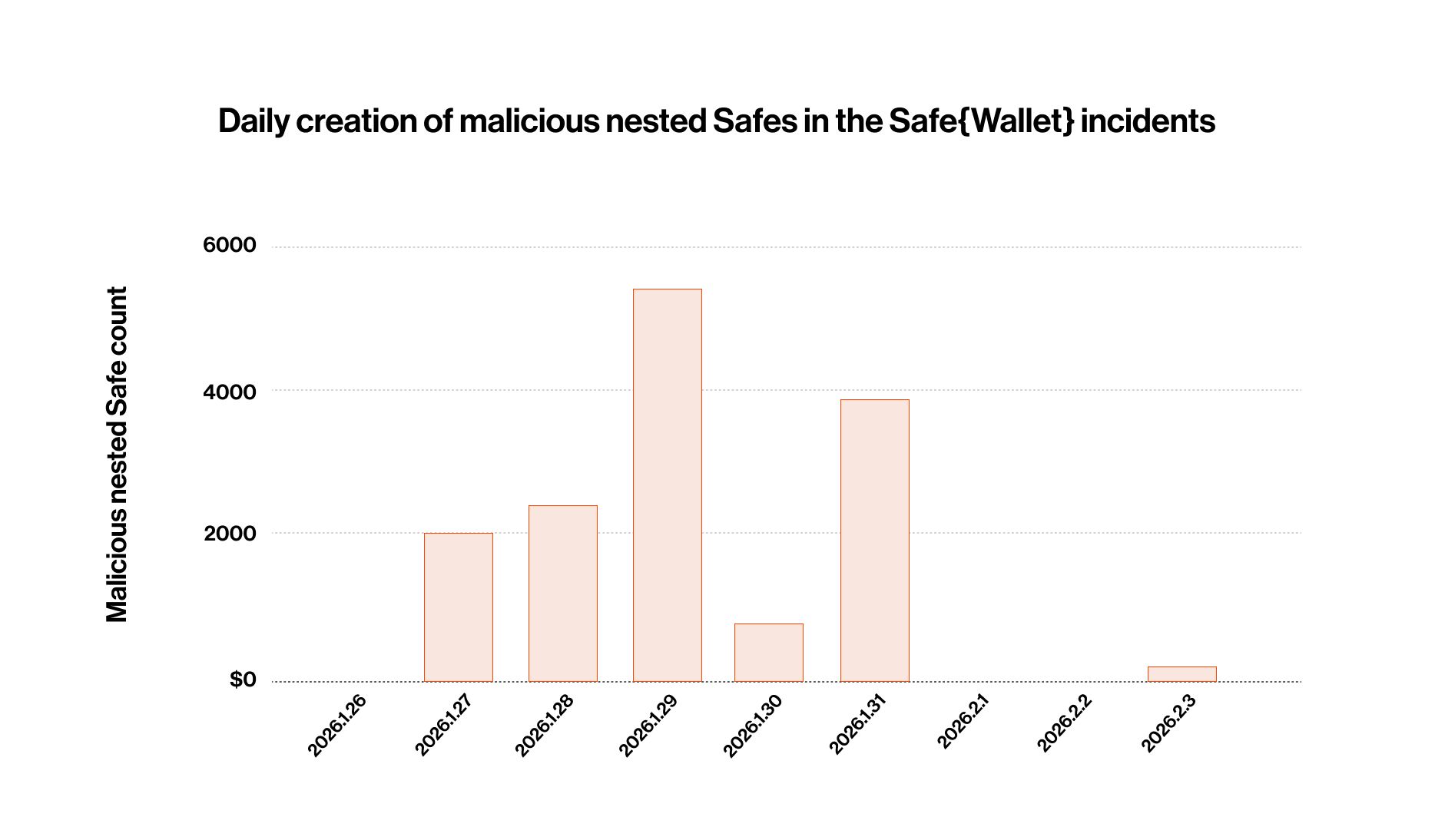

In 2025 and early 2026, we've tracked an escalation in both the frequency and sophistication of these attacks. A single copy-paste mistake now routinely costs victims millions of dollars, and attackers are continuously refining their methods to bypass the defenses the industry has put in place. It is illustrated by a recent sophisticated address poisoning campaign targeting Safe{Wallet} users. Attackers exploited the platform's nested Safe feature to bulk-create ~15,000 malicious proxy addresses with lookalike addresses, planting them directly in victims' wallet UIs. Our collaboration with the Safe team to detect and mitigate this campaign revealed just how far address poisoning TTPs have evolved — and prompted a broader look at the threat landscape.

How Address Poisoning Works

Address poisoning exploits a fundamental tension in how blockchain wallets work: addresses are long, hexadecimal strings that are practically impossible for humans to memorize or visually verify in full. Most users rely on checking just the first and last few characters of an address, and many copy addresses directly from their wallet's recent transaction history.

Attackers exploit this workflow in a few steps:

- First, they identify a high-value target and analyze their transaction patterns to find frequently-used destination addresses (exchanges, OTC desks, cold wallets).

- Next, using specialized vanity address generators, they create an address that matches the first and last several characters of the legitimate address.

- They then send small "dust" transactions — often fractions of a cent — from this lookalike address to the victim's wallet, embedding it into the victim's transaction history.

- When the victim later goes to make a transfer and copies an address from their recent transactions, they may grab the poisoned address instead of the real one.

The attack requires no technical exploitation of any smart contract or wallet software. It targets the most vulnerable layer of the stack: human behavior.

Address Poisoning in Numbers

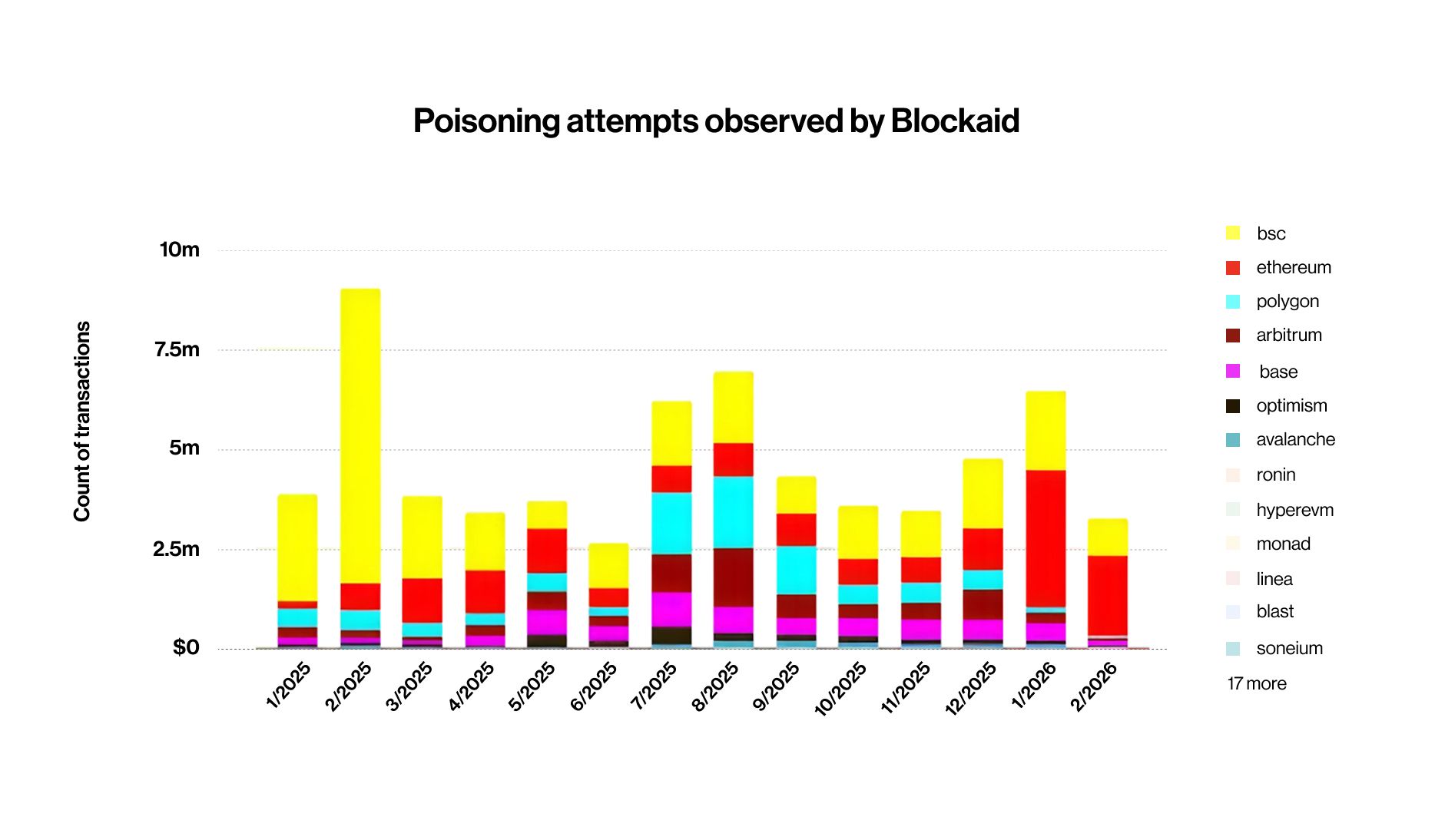

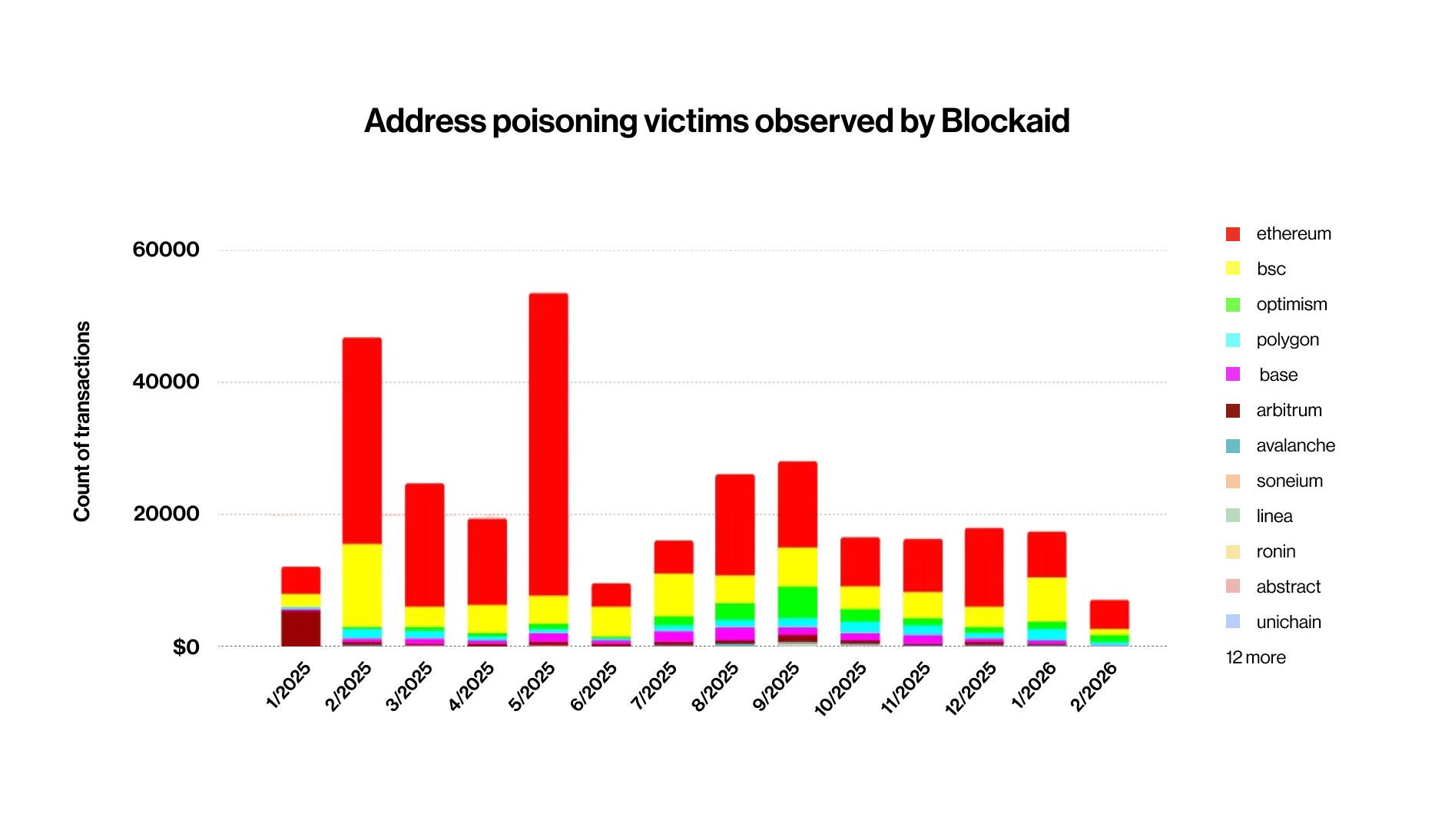

Since January 2025, Blockaid has flagged over 65.4 million address poisoning transactions on-chain — averaging more than 160,000 per day. Of those, approximately 316,000 were confirmed attacks where victims actually sent funds to a poisoned address, meaning roughly 1 in every 200 poisoning attempts succeeds.

The problem is accelerating: Ethereum's Fusaka upgrade on December 3, 2025 reduced transaction fees by roughly 6×, removing the primary economic brake on mass poisoning campaigns. Following this, January 2026 in Blockaid’s data on-chain saw poisoning attempts spike from 628,000 in November 2025 to 3.4 million in January 2026 — a 5.5× increase in just two months. By January 2026, Ethereum had overtaken BSC as the single most poisoned chain in our dataset for the first time. This directly validates what external researchers observed: Coin Metrics found that stablecoin dust surged from 3–5% to 10–15% of all Ethereum transactions post-Fusaka, with a single attacker contract sending approximately 3 million dust transfers to over 1 million unique addresses for just $5,175 in total cost.

TTPs Are Getting More Sophisticated

What's striking about the address poisoning landscape in late 2025 and early 2026 is not just the scale, but the increasing sophistication of attacker tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). Several recent developments illustrate this evolution.

Test Transaction Interception: Weaponizing the User's Best Defense

Sophisticated attackers now run bots that monitor the mempool and on-chain activity for small "test" transfers — the exact security practice that users are taught to follow before sending large amounts. When a test transaction is detected, the bot immediately generates a lookalike address, sends a dust transaction to plant it in the victim's history, and waits for the follow-up high-value transfer.

The $50 million USDT loss in December 2025 is the clearest example: the attacker detected a $50 test transaction, planted a spoofed address, and the victim sent 49,999,950 USDT to the poisoned address just 26 minutes later. This technique is especially dangerous because it specifically targets security-conscious users.

Long-Term Dusting Campaigns

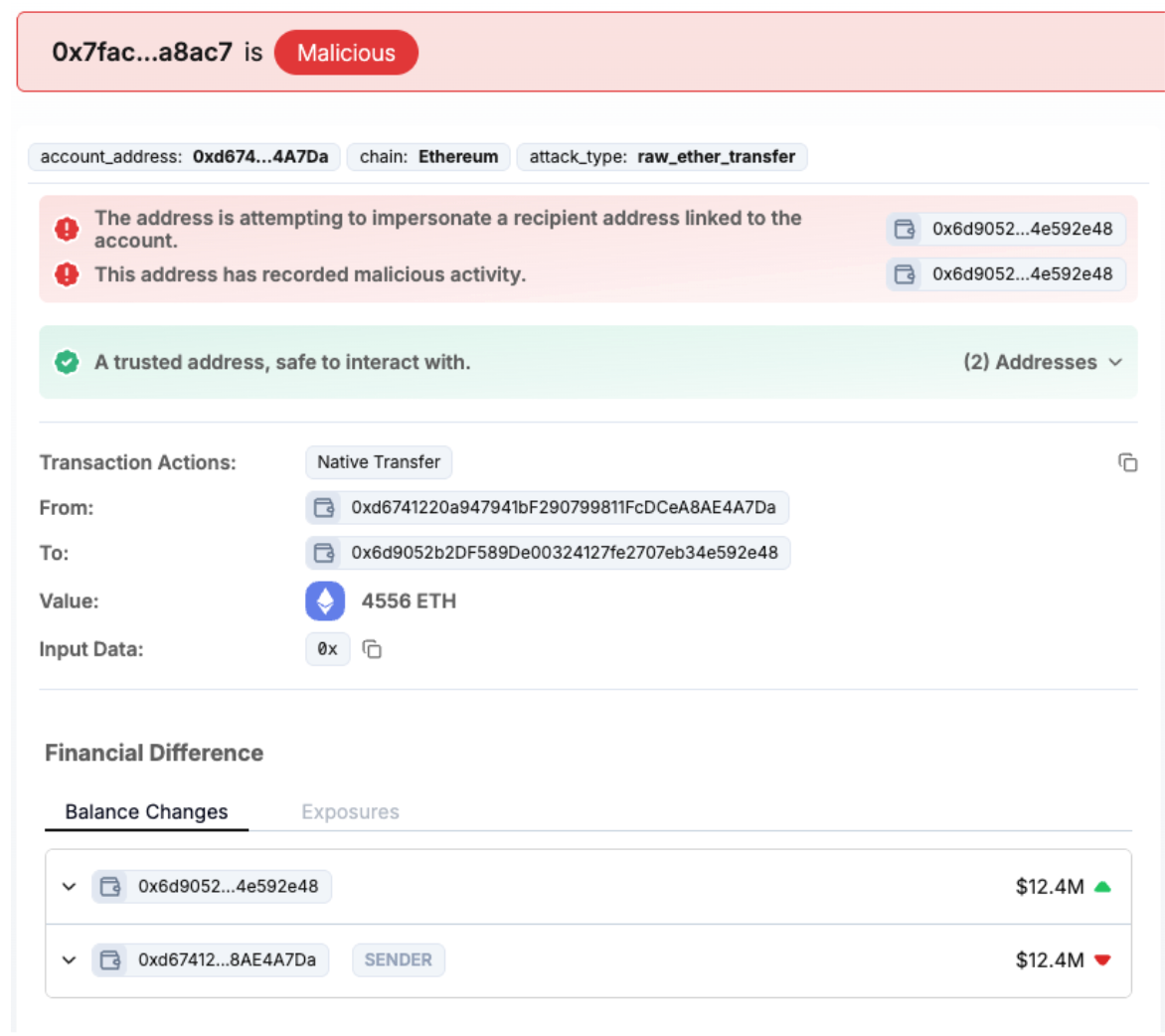

On January 30, 2026, a cryptocurrency holder lost 4,556 ETH — approximately $12.4 million — in what appeared to be a routine transfer to their OTC deposit address. The attacker had been systematically dusting the victim's wallet for over two months, from December 2025 through January 2026. They generated a vanity address (0x6d9052b2...e592e48) that closely matched the victim's legitimate OTC address (0x6D90CC8C...DdD2E48) in both prefix and suffix. Over the campaign period, the attacker sent multiple dust transactions to the victim, ensuring the poisoned address remained visible in their recent transaction history.

Approximately 32 hours before the theft, the attacker conducted a final dusting operation to push the malicious address near the top of the victim's transaction history. The victim, likely intending to deposit to their OTC address, copied the poisoned address instead.

This case highlights a key evolution in attacker patience and operational discipline. Rather than spraying dust broadly and hoping for the best, this attacker conducted sustained reconnaissance, identified a specific high-value transaction pattern, and timed their campaign to maximize the chances of the victim selecting the wrong address.

Exploiting Platform-Specific Features: The Safe Nested Proxy Campaign

The most sophisticated campaign we investigated in this cycle targeted users of Safe{Wallet}, the widely-used multisig platform. Rather than poisoning transaction history, attackers exploited a specific product feature: nested Safes.

As detailed by the Safe team, the platform allows any user to create a new Safe and add an existing Safe as one of its owners. When this happens, the newly created Safe automatically appears in the parent Safe's UI as a "nested Safe" — even though the parent Safe's signers never created or authorized it. Attackers exploited this by bulk-creating malicious Safes since at least January 26, 2026, with lookalike addresses closely matching the victim's legitimate nested Safes. They then pre-signed drain transactions on these malicious Safes so that any funds sent to them would be immediately siphoned to an attacker-controlled wallet.

What made this particularly dangerous was the positioning: unlike standard poisoning, which relies on a user copying an address from transaction history, nested Safe poisoning plants the malicious address right next to the original parent Safe in the UI. For teams that frequently create and manage sub-accounts, this was nearly indistinguishable from a legitimate nested Safe.

Blockaid's research team identified approximately 15,000 malicious proxy addresses created through this campaign. We worked closely with the Safe team to flag all identified addresses through our security infrastructure.

This trend — attackers studying the specific UX patterns and features of popular wallet products to find new injection surfaces beyond transaction history — is something we expect to see more of in 2026.

The Supply Chain: Cybercriminals Democratizing Address Poisoning

Blockaid observed a dedicated cybercriminal supply chain for address poisoning, making reconnaissance, vanity address generation and transaction scripting available as turnkey tooling for low-skilled attackers.

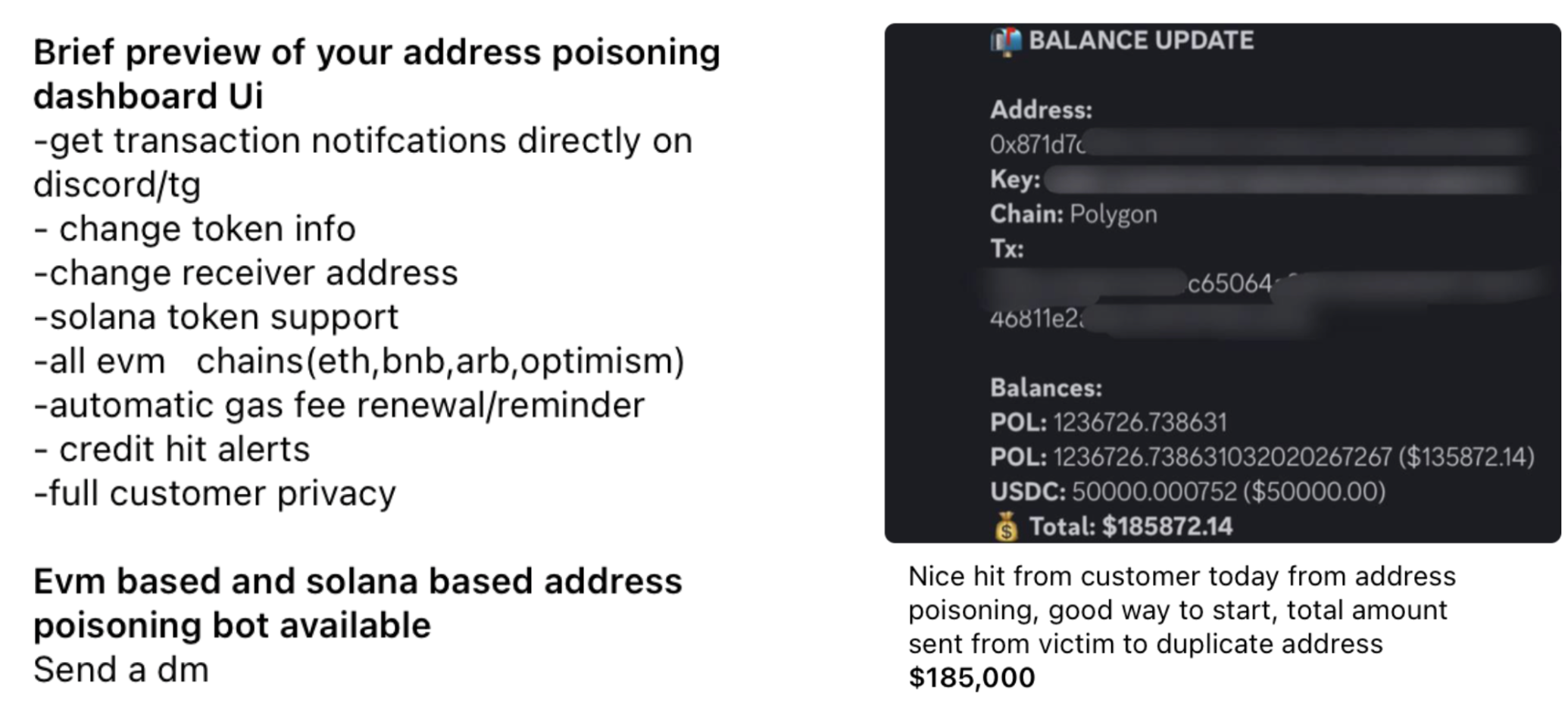

For example, there is a group operating on Telegram that sells address poisoning bots and services, in addition to allegedly operating their drainer on multiple chains (Ethereum, BNB Chain, Arbitrum, Optimism and others). They advertise EVM-based and Solana-based address poisoning bots, complete with a dashboard UI, boasting that "poisoning attacks have the biggest hits so far." The actor claims that one of their customers earned around $185,000 through one transaction.

Messages from the actor’s group offering address poisoning bots

Blockaid has also found a Telegram bot specifically built to automate Solana-based address poisoning. The bot lowers the barrier to entry to nearly zero by walking users through the entire attack lifecycle:

- Target selection guidance: The bot instructs users to find targets on DexScreener or Pump.fun by identifying top token holders with significant funds — while warning them to avoid liquidity pools and centralized exchanges.

- Reconnaissance assistance: Users are guided to open target wallets on Solscan, verify human-like transaction activity, and identify side wallets that interact frequently with the victim's central wallet.

- Automated vanity address generation: Users choose a "level of poisoning similarity" (how closely the generated address matches the target), and the bot generates the poisoned address automatically.

- One-click poisoning: A dedicated function allows users to send small amounts of SOL or tokens to their poisoning address, which the bot then redirects to the victim's wallet — embedding the poisoned address in the victim's history.

- Automatic payout: Any amount above a threshold sent by the victim to the poisoned address is treated as a successful hit and forwarded to the attacker's exit wallet.

The bot claims to collect around $15,000 USD in SOL, indicating that the operation is probably in an earlier stage.

The existence of such tools means that address poisoning is no longer the exclusive domain of sophisticated attackers. Critical components of the address poisoning kill chain are openly available on GitHub, lowering the barrier even further, such as vanity address generators and end-to-end attack toolkits, packaging automatic blockchain scanning, vanity address generation, fake USDT contract deployment, and automated transaction crafting into a single tool and framed as "security research."

Recommendations

Address poisoning thrives on shortcuts in human behavior. Defending against it requires both user discipline and better tooling from wallet providers.

For users

- Never copy addresses from transaction history. Always retrieve the recipient address from a verified source — an address book, a bookmarked page, or direct confirmation through a separate channel. This single habit eliminates the primary attack vector.

- Use your wallet's address book. Save and label verified addresses for frequent recipients. This removes the temptation to pull addresses from transaction history.

- Verify the full address, not just the first and last characters. Attackers specifically design their vanity addresses to match the characters most people check. Verify at least the middle portion of the address as well.

- Send a small test transaction first — and verify receipt through a separate channel. For high-value transfers, confirm with the recipient through a different communication method (phone call, encrypted messaging) that the test transaction arrived at the correct address. Note: sophisticated attackers have been observed poisoning history immediately after test transactions, so a test alone is not sufficient without independent verification.

- Be suspicious of unfamiliar addresses or accounts appearing in your wallet UI, especially nested accounts, sub-wallets, or newly-appeared contacts that you didn't explicitly create.

For wallet providers and platforms

- Flag and filter known poisoned addresses using security partners that maintain real-time threat intelligence on address poisoning campaigns.

- Warn users when they copy addresses from transaction history rather than from a verified address book.

- Audit product features for poisoning attack surfaces. Any feature that allows external actors to inject content into a user's wallet UI (transaction history, nested accounts, address suggestions) is a potential vector.

- Implement visual address differentiation that goes beyond first/last character matching that makes it easier for users to recognize legitimate addresses at a glance.

Blockaid is securing the biggest companies operating onchain

Get in touch to learn how Blockaid helps teams secure their infrastructure, operations, and users.